|

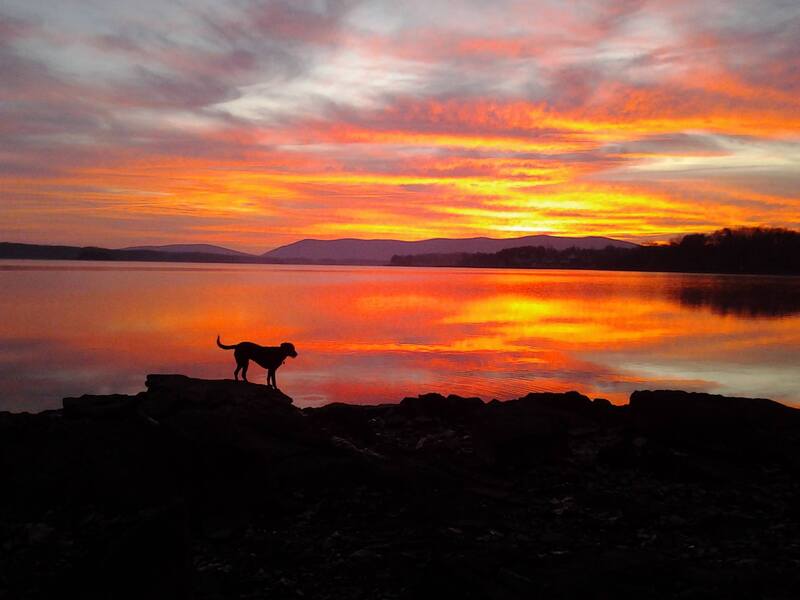

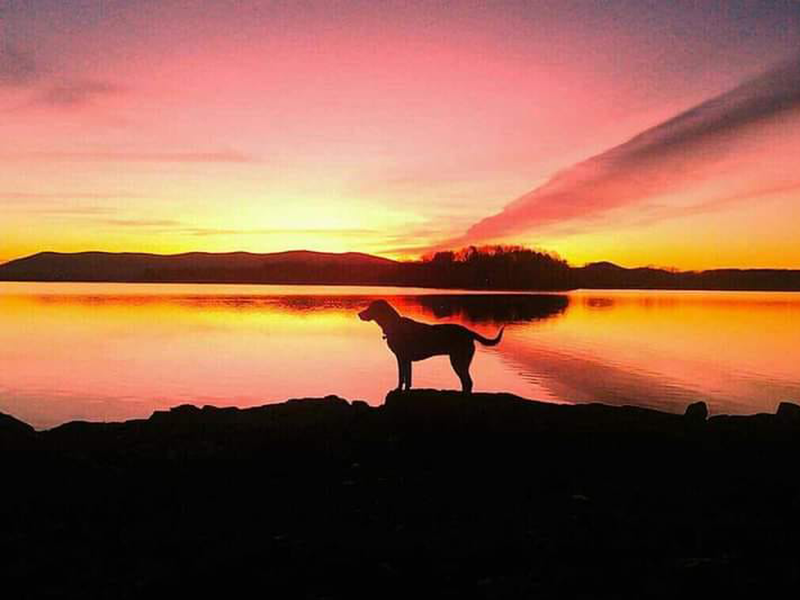

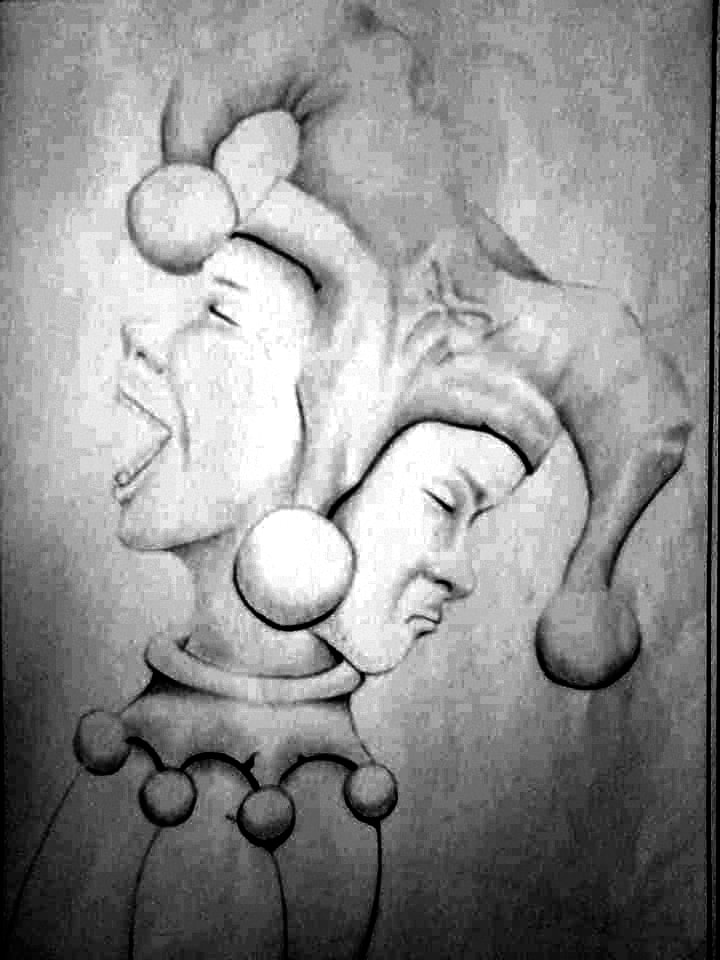

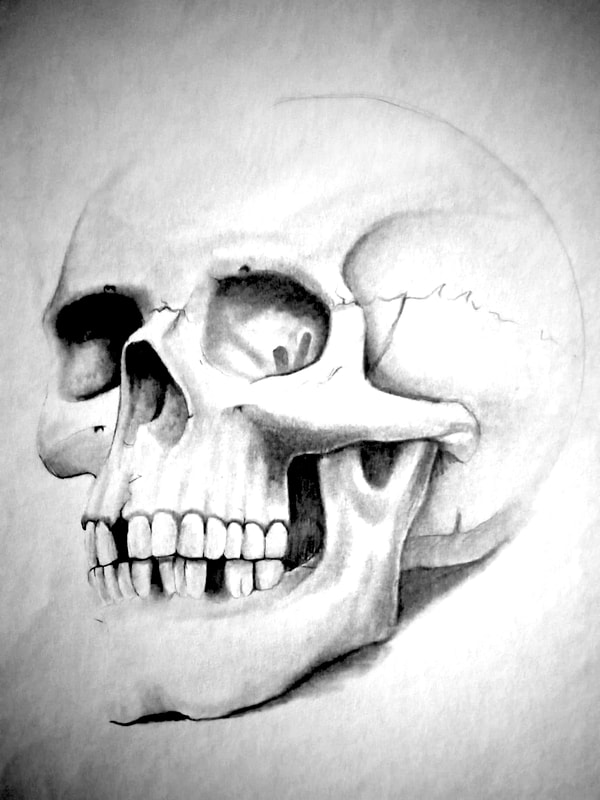

Resident Travis Trout has spent over two decades of his life in incarceration, yet his discovery of art while in prison has given him a lifeline of hope for the future.  Travis Trout, Resident Travis Trout, Resident Travis Trout, 42, arrived at Gemeinschaft Home in late August and has spent much of his first month in the program experiencing an uncomfortable yet familiar reality—adjusting to life after prison. The leap from day-to-day existence in prison to the chaotic world outside is far more difficult than many people understand. For Trout, someone who has spent about half of his forty-two years behind bars, the process has been a life-long revolving door, with each turn as de-stabilizing as the one before it. Trout’s mother passed away when he was only 13 years old, which had a shattering impact on his development as a young adult. He went to live with his grandparents on Smith Mountain Lake, in southwestern Virginia, where he grew up, but was soon arrested at the age of 14 on a burglary charge. He had broken into a vacated house—damaging a window in the process—an action that precipitated continual interactions with the criminal justice system. At age 17, he was incarcerated for two years in a juvenile facility; so, by early adulthood, Trout already had more than an acquaintance with life as an inmate. He has no violent criminal history, but economic pressure combined with a lack of guidance, led to Trout’s early association with drugs and other low-level crimes, usually involving short sentence terms, followed by community supervision (probation). Between prison stays, he has always tried to live a “normal” life, forming relationships, having children, and trying to get by like everyone else, but he faced significant struggle doing so. He violated the conditions of his probation—such as failing a drug screen—on several occasions which nearly by default landed him back in prison. In fact, over a decade of the time Trout has served was the result of a technical violation of his probation, rather than a new conviction. However, each time he has gone to prison, the de-stabilizing force on his life outside has become more pronounced—the effects of which he especially feels now as a resident in the Gemeinschaft Home program. “The simplest things for most people are the biggest things for me,” Trout explains, pointing out that the highly-structured lifestyle of prison was easier to manage in certain ways. While he lacked basic independence and freedom of movement, he was also granted freedom from the inevitable responsibilities of the outside world—securing a home and stable employment, paying bills, and negotiating a range of daily obstacles that challenge us all. During times of crisis, he has wished to be back in prison, where he argued that he could control his environment and manage expectations of his behavior with more ease. He recalls one such conversation with his probation officer, about 10 years ago, when his uncle had just passed, and he felt his life spinning out of control. He asked her bluntly, “Can you just put me back in jail so I can regroup?” as he planned to purposely fail a drug screen. He felt similarly adrift when he lost both grandparents as well. It was the same pattern he had grown accustomed to over the years. As of August, Trout is again free from incarceration, and he now faces the same obstacles that have always confounded his ability to live beyond the institutional confines of prison. And, while 90 days at Gemeinschaft Home is a start, he has a chance to gain tools to stop the revolving door and to make the permanent transition out of prison. One way he hopes to do so is through his artwork. Ironically, Trout discovered his artistic abilities many years ago, while incarcerated—at first just some basic pencil sketches, but later more developed drawings that he crafted in finer detail. What started as a way to combat boredom quickly became a passion, and with no (or very little) formal training, Trout found a creative outlet that continues to thrive. He also cultivated a proficiency in both designing and applying tattoo art, work that he has continued to pursue both inside and outside of prison. Yet, as an evolving artist, he started to notice how incarceration had changed the way he saw the natural world, and he developed a quick and profound interest in digital photography. “After being locked up so much, when I spent time outside of prison, I started noticing leaves, looking at bugs...seeing things in nature that I never paid attention to,” he says, and he started taking pictures when he was free to roam around and explore. Over the years, he has built a significant collection of drawing and photos, some of which are featured here. Drawing and photography supply a sense of balance in Trout’s life, offering a source of personal growth and a means of creative expression. He hopes to make art an important part of his journey forward to a life that is much too large for the confines of a prison cell. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

August 2023

|